The Lincoln Highway the Story of a Crusade that Made Transportation History

The Lincoln Highway Association 1935

249 pages

Living in an age of hermetically sealed automobiles and wide interstate freeways it’s hard to consider what it was like before we got here. Then as we walk around Donner Summit, perhaps holding a copy of the DSHS’s “Lincoln Highway” brochure, we can see the route of the first transcontinental highway and a number of pristine sections. We take it for granted that people came along, wanted better travel routes, and the Lincoln Highway was born. We shouldn’t take the idea for granted, nor the old highway.

The Lincoln Highway the Story of a Crusade that Made Transportation History was published in 1935, only two decades after the road was established. It was written and published by the Lincoln Highway Association (LHA). Because it was done by the LHA it’s a self-congratulatory volume highlighting the spirit, energy, work ethic, etc. of the principal characters. “Here, in one sentence, is the secret of the marvelous results attained by the Lincoln Highway, the thing that kept men working day and night, year after year, to make it a success. Each man had his work to do and the man higher up not only let him do it but expected him to do it."

Here are some other examples, “ALL [capitalized in the original text] Lincoln Highway men were public-spirited. The local consul in the smallest community on the route and the president of the organization alike were enthusiastic, able to visualize what real highways could be and willing to labor endlessly and unselfishly to create them.”

“Having material of such temper [the people involved] available, it is not surprising that President Joy and Secretary Pardington fashioned from it one of the most effective organizations ever created. In this organization local rights were protected”

Then because everyone had to be recognized, the appendix has lists of names and throughout the book there are pictures of many of the principles.

Then because everyone had to be recognized, the appendix has lists of names and throughout the book there are pictures of many of the principles.

That’s not to say that the congratulatory remarks are bad, it’s just that there are a lot of them and they don’t add to the story. There is also a lot of information in the book.

Carl Fisher invented carbide lamps for automobiles. He also invented the Indianapolis speedway which was a “proving ground or makers of motor cars…” So he was associated with automobiles for a long time. His biggest idea was the Lincoln Highway, “A road across the United States; Let's build it before we're too old to enjoy it." In 1912, when Mr. Fisher presented his idea, there were almost no roads in the country, “as roads are known today [1935]” Only 28 of 48 states spent anything on roads. Road signs were a rarity.

The impetus for the idea of the national highway came from an incident where Fisher and two friends drove out from Indianapolis. As it got dark it started to rain hard and the car had no top so the group headed back. Coming to a three-way intersection they had no idea which way to go. They could see no city lights to guide them and “It was black as the inside of your pocket.” Using their headlights Fisher climbed a pole where he’d seen a sign which couldn’t be read from the ground. At the top he pulled out his matches so he could light the sign, “Chew Battle-Ax Plug.” Something had to be done about roads.

It was also a time when roads were a local thing rather than built with Federal or even state government money. Hence, Carl Fisher began a national movement to build a transcontinental highway, made of concrete, bypassing the various governments.

Fisher first turned to the automobile industry because without roads there would be no market for their cars. Then he turned to the concrete industry because it would have a big interest in the endeavor. Fisher aimed for completion of his national road by 1915 so that 25,000 people could drive to the 1915 World Exposition in San Francisco. Knowing that individual people might want to participate in the building of the transcontinental highway, memberships were offered.

Initially the project was paid for with individual subscriptions/memberships and subscriptions from businesses and industry. The auto and cement industries for example promised .5% of gross business for three years.

The book goes on to talk about the inner workings of the planning group, discussions about various aspects of the project, raising money, initial and continuing publicity, details of the 1919 army convoy (initiated and done with the assistance of the LHA), races or record setting automobile trips across the continent, fights over the route, a recalcitrant state, etc.

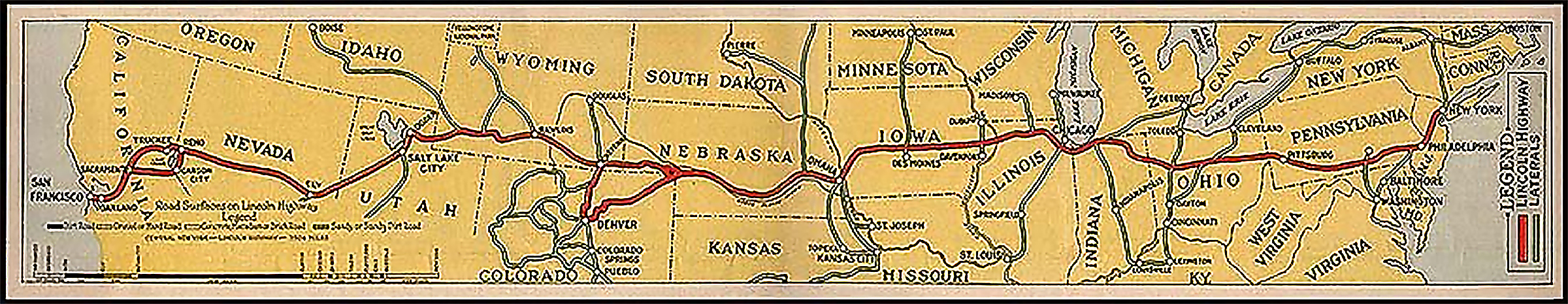

During the discussion of the route the conclusion was that the best route had been chosen. That leads us to Donner Summit. The Lincoln Highway Association chose to follow the Pony Express route because it worked and was the “acme of highway construction, the route of the Overland Stages.” That took the route over Echo Summit to Placerville and then Sacramento and beyond. They also chose the Donner Summit route but there is no discussion about why two routes, the only place in the entire transcontinental route where there was an alternative, were chosen and why they focused on the Pony Express route instead of the railroad’s route in their initial publicity. We should note too that for the stage company that was a competitor to the Overland Stage, the "acme of routes," was over Donner Summit. (See our August, ’19 Heirloom to see that the Truckee route was superior; but of course all Heirloom readers already know that so this note is kind of irrelevant).

It’s interesting to note that common knowledge says that the Lincoln Highway was born in 1913 using existing roadways. According to the LHA, the authors of this book, 1913 really was just the start of public fundraising and that’s when the membership drive started – after the route had been laid out. $5 Memberships were sold primarily by motor car dealers and good roads enthusiasts and supplemented with direct mail. There were also donations of ad space in various magazines and journals. A solicitation to “3,000 millionaires [met] with but negligible results” though.

It was a huge endeavor made harder by selfish interests competing to be on the route; a continued lack of money; the need to conduct a continual public relations campaign; competition for public attention with WWI, the Panama Canal (just finished in 1912), and even the exposition in San Francisco in 1915. Clearly the Lincoln Highway was not something to take for granted.

In California there were fights over whether the road should go to Los Angeles instead of San Francisco and whether Beckworth Pass or near Yosemite would be better than what was decided as the route to cross the Sierra – the Placerville and Auburn routes.

Sometimes the detail is as tedious as it was self-congratulatory. There are lots of lists of articles about the highway in so many places by so many people. Then, in the discussion about “seedling miles” there are lists describing the miles across the country. The authors could just have said there were lots of articles about the highway and “seedling miles” were a great idea that helped the effort. The reader doesn’t need to know about each one.

Within a few years money began to flow from the Federal Government, standards were published, and “traffic was increasing by leaps and bounds…” The principles do need to be recognized; the first transcontinental highway was a boon to the nation.

Here’s how travel was before the Lincoln Highway:

Henry B. Joy, President of the Packard Motor Car Company, took many of these test trips himself, often through some terrible conditions. Once, plodding through a test trip, he asked the Packard distributor in Omaha for directions to the road west.

“There isn't any," was the answer.

"Then how do I go?" asked Mr. Joy.

"Follow me and I'll show you."

They drove westward until they came to a wire fence. "Just take down the fence and drive on and when you come to the next fence, take that down and go on again."

"A little farther," said Mr. Joy, "and there were no fences, no fields, nothing but two ruts across the prairie." But some distance farther there were plenty of ruts, deep, grass-grown ones, marked by rotted bits of broken wagons, rusted tires and occasional relics of a grimmer sort, mementoes of the thousands who had struggled westward on the Overland Route in 1849 and '50, breaking trail for the railroad, pioneering the highway of today.